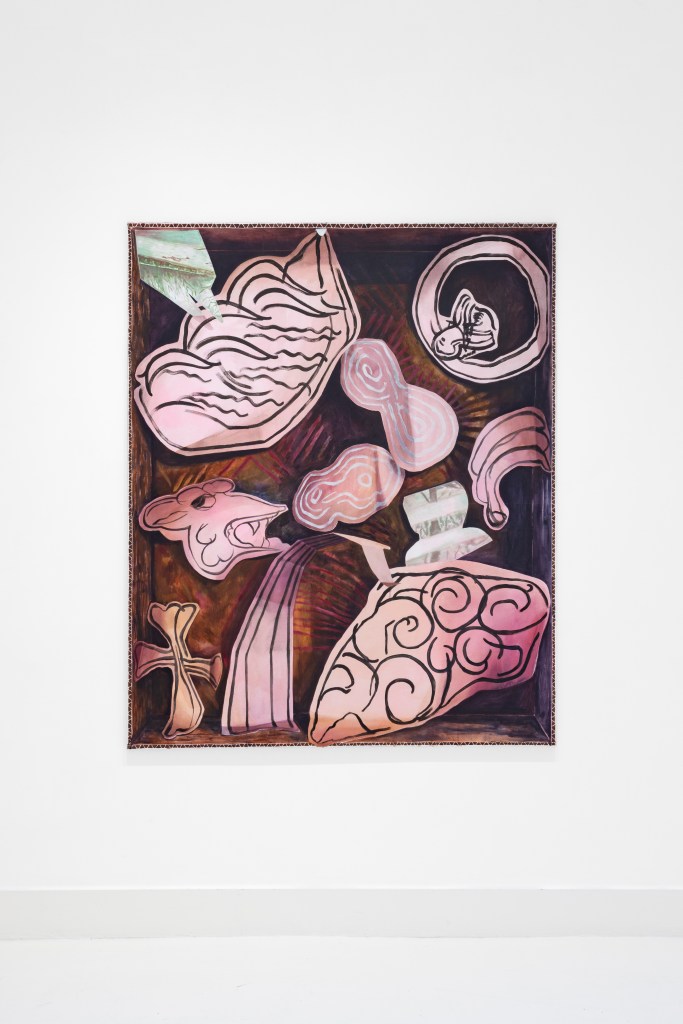

If an artist works best in solitude, a certain adaptation is required when a baby gurgles in the corner (on a blanket laid over layers of bubblewrap). It is still a sort of solitude, despite the baby, as the baby does not question, judge, smirk, compliment, theorise – but the baby does demand (and distract). The baby demands to be held and comforted – and depending on the type of baby – may also require a small cave to be formed over its prone form at periodic intervals. Absolute quiet is advised (no canvas stretching, no slamming doors). At other times, they may wish to be held and not put down at all and so the artist is forced to contemplate their work; their next brushstroke, pencil mark, stitch for perhaps an hour, maybe more. If the artist is a very fast worker and throws speed at every studio activity, a forceful slowing down ensues. Decisions line up in a queue to be ticked off at the next nap, doubt forms from overlooking, questions build up where no questions formally lay. And sometimes (rarely) a problem solves itself quite happily from time being spent in thoughtful contemplation.

Different negotiations have to be made when the baby learns to crawl. Once a baby is mobile, items at a certain height have to be moved upwards as the slightly loosened caps on paint tubes may end up in the mouth of an exploratory baby. This is tricky if the solitude-loving artist works on the floor. Explorative babies seem to love finding the most dangerous object in the studio (cadmium red, an unsheathed knife) and playing with it. Periodic health and safety checks are advised. The biggest issue, however, arises from the regularisation of the nap. Perhaps people who don’t come into contact with babies might roll their eyes at schedules and parenting obsessions with time (the author might have been such a person once) but unfortunately even the most bonnie, benign baby prefers certain atmospheric conditions to sleep in (pitch black room, absolute silence, screaming for the eleven minutes prior). Studio neighbours are made intimately aware of the baby’s presence as their own solitude is impinged upon. These neighbours might regularly assure their fellow artist, “The sound doesn’t bother me at all.”

At this stage (baby is 7-9 months of age), the solitude-craving artist will reach a crossroads. There are the conditions at home which perfectly complement the baby’s needs and the conditions in the studio which become something of an obstacle-course-cum-testing-ground. There is weaning to consider and plan for, there is the temperature of the studio (freezing or boiling, un-heatable or un-coolable), there are entertainment needs (toys fast become dull) and suddenly the baby-adapted solitude the artist perfected for the baby’s life thus far, is no longer workable. Once the baby becomes a toddler, this resolve is further tested.

When the baby is nine months old the artist may have a solo exhibition with the work made during the baby’s naps (on the days when their other toddler is at nursery thanks to the 30 hours free childcare for working parents). In the short, ensuing break the baby is now nearly also a toddler and it is deep-midwinter. Attempts to return to the studio might fast prove that solitude is no longer remotely possible. The baby has become an individual, a person, and yes, there is now judgement and criticism expressed volubly and regularly.

But as of new legislation in 2025 (eligible for working parents the term after the baby turns 9 months), the baby-toddler can join their sibling at nursery (thanks to the 30 hours free childcare for working parents) and so the artist resolves to wait for true solitude to resume their practice in January 2026. God willing.

–

Strongly recommended tools for additional solitude: a partner to share childcare on the five other days not covered by 30 hours free childcare for working parents, grandparents (for similar reasons) and should an artist be so lucky, voluminous wealth might also be a boon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.